Manta ray (Manta alfredi) tourism in Baa Atoll, Republic of Maldives: human interactions, behavioural impacts and management implications

2011

Rebecca Atkins (MSc Marine Environmental Management - University of York)

Summary: This study focused on human-manta interactions in Baa Atoll, Maldives, where manta ray tourism is significant. Video footage of 407 interactions at feeding aggregations and cleaning stations was analysed. The results showed that most participants behaved responsibly and did not disturb the mantas. Human behaviours included passive observation, following, accidental obstruction, and intentional contact, while manta response behaviours included avoidance and flight. Behaviours prone to disturbance can be addressed through a manta Code of Conduct. With proper management of human interactions, manta ray tourism in the Maldives can be a sustainable and viable alternative to fishing, benefiting both tourists and local communities.

Abstract

“Encounters with marine animals provide tourists with a unique and memorable wildlife experience and can make considerable economic contributions to local communities. The large population of mantas within the Maldives, and the predictability of certain aggregations, has allowed the development of a significant manta ray tourism industry. Previous observations of tourism impacts on mantas in the Maldives, however, have highlighted issues of concern, and there is evidence that tourism pressure on the resident manta ray population is increasing. Therefore, the impacts of human encounters on mantas and associated levels of disturbance need to be assessed.

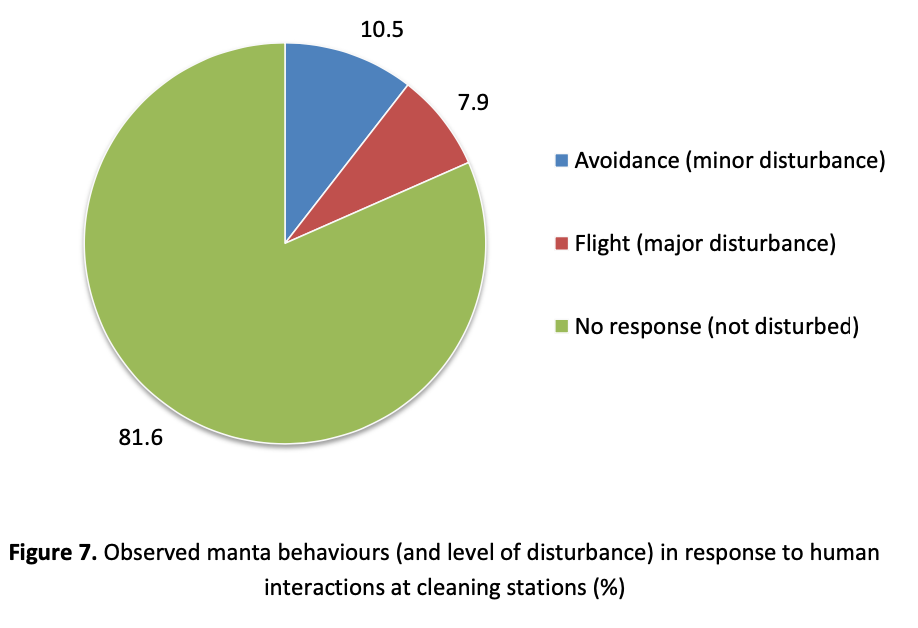

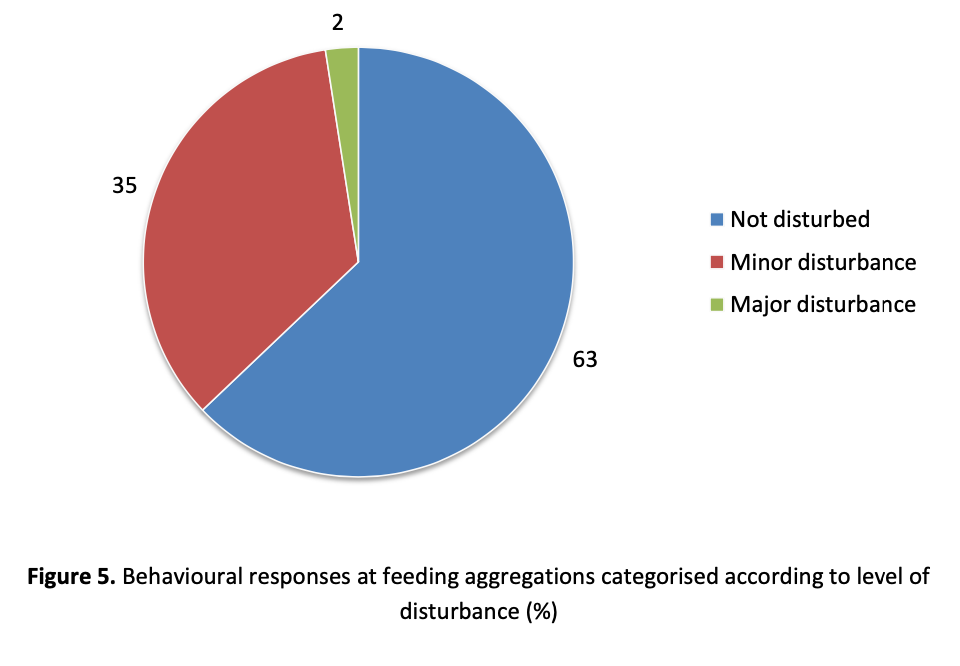

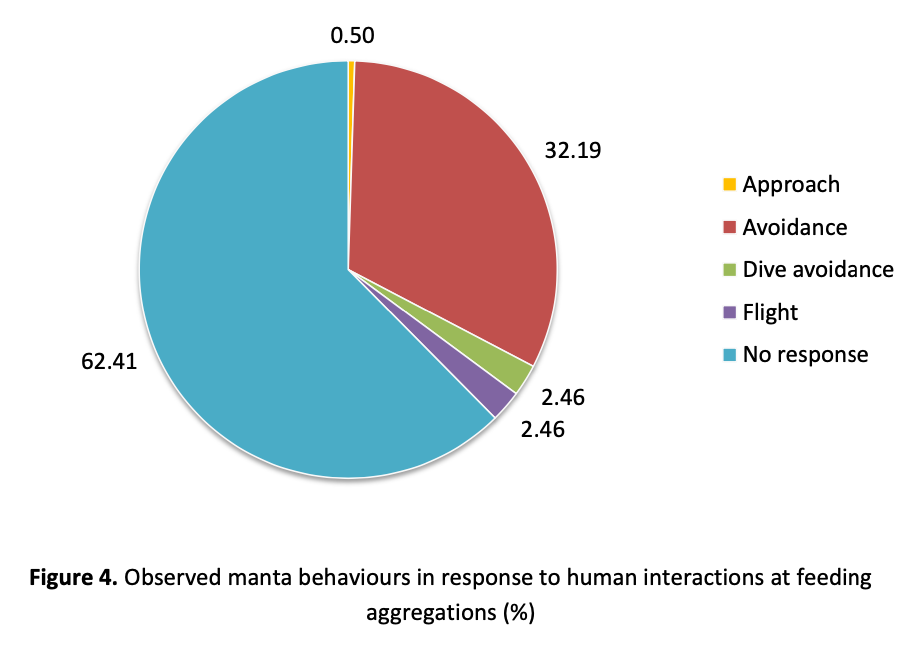

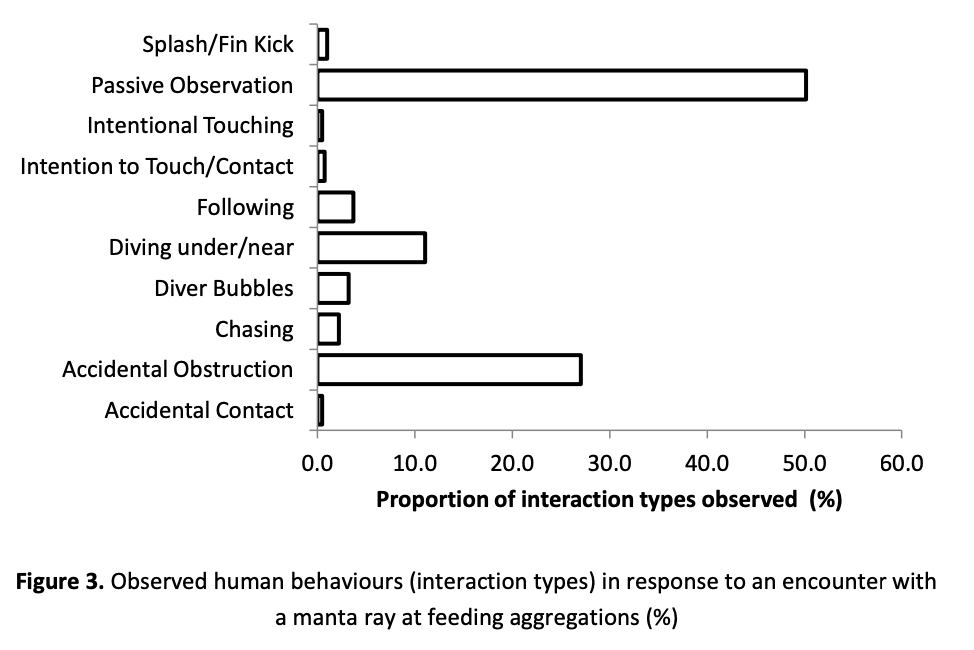

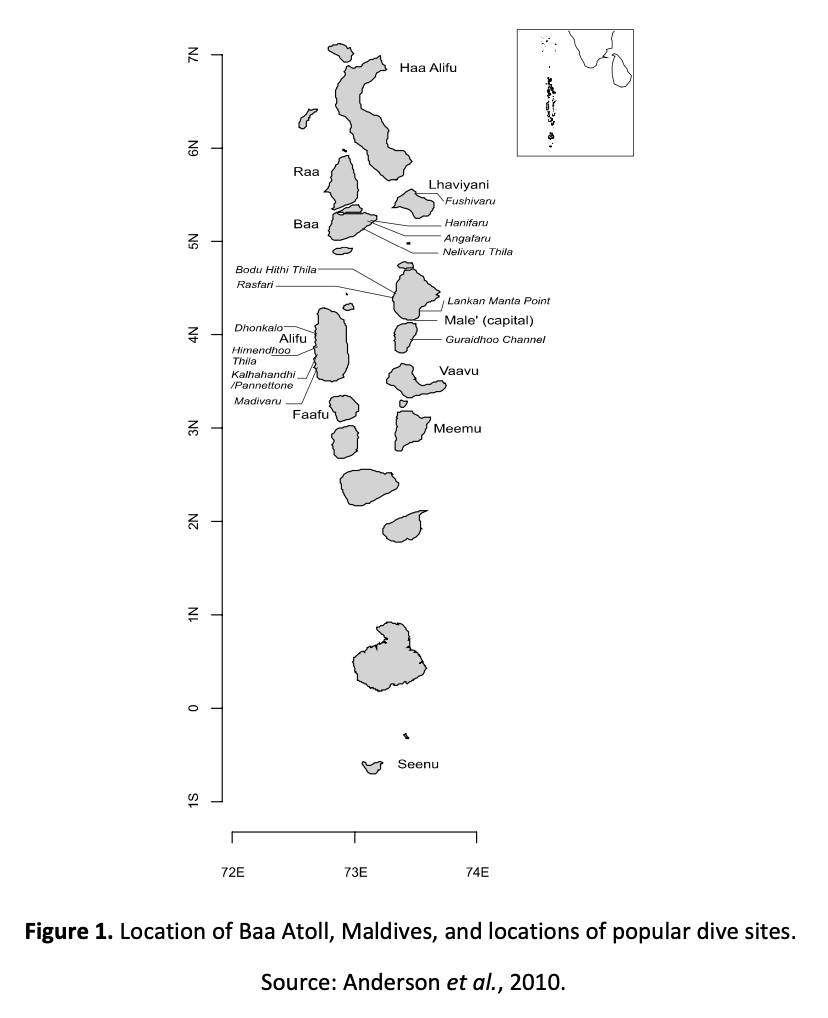

This study examined video footage of human-manta interactions at six feeding aggregations, and six cleaning stations, in Baa Atoll, Republic of Maldives. Video footage captured divers and snorkelers interacting with mantas, with a total of 407 unique human-manta interactions from 138 encounters analysed from feeding aggregations, and 38 unique human-manta interactions from 11 encounters analysed from cleaning stations. Human behaviours in response to manta encounters included passive observation, following, accidental obstruction, diving under or near a manta, and intentional contact. Mantas response behaviours included avoidance and flight behaviours.

The results of this study showed that the majority of participants in manta ray tourism in Baa Atoll behave in a responsible and non-disruptive manner, and the majority of interactions do not result in manta disturbance. Behaviours prone to causing disturbance can be mitigated for by inclusion in a manta Code of Conduct. Although further research is required to aid our understanding of the impacts of repeated disturbance on the longer-term health status and survival of mantas, Manta ray tourism in the Maldives, with appropriate management of human interactions, can represent a long-term and sustainable tourism practice, and a viable alternative to fishing.”

Author Affiliations

University of York

The Manta Trust