Does tourist behaviour affect reef manta ray feeding behaviour? An analysis of human and Manta alfredi interactions in Baa Atoll, the Maldives

2016

Ella Garrud (MSc Marine Environmental Management - University of York)

Summary: The popularity of swimming with marine megafauna in the Maldives has increased, particularly with manta rays. However, the presence of large numbers of tourists at popular sites may negatively impact the natural behavior of reef manta rays. This study examined the interactions between humans and manta rays by analyzing video footage from five feeding sites in Baa Atoll, Maldives. The findings showed that passive observation of the mantas had a positive effect, while obstructing their path or approaching them from the front increased avoidance behavior. Maintaining a minimum distance of 3 meters and following specific guidelines, such as approaching from the side, were recommended to minimize disturbance. These findings support the Manta Trust Code of Conduct for Tourism Interactions.

Abstract

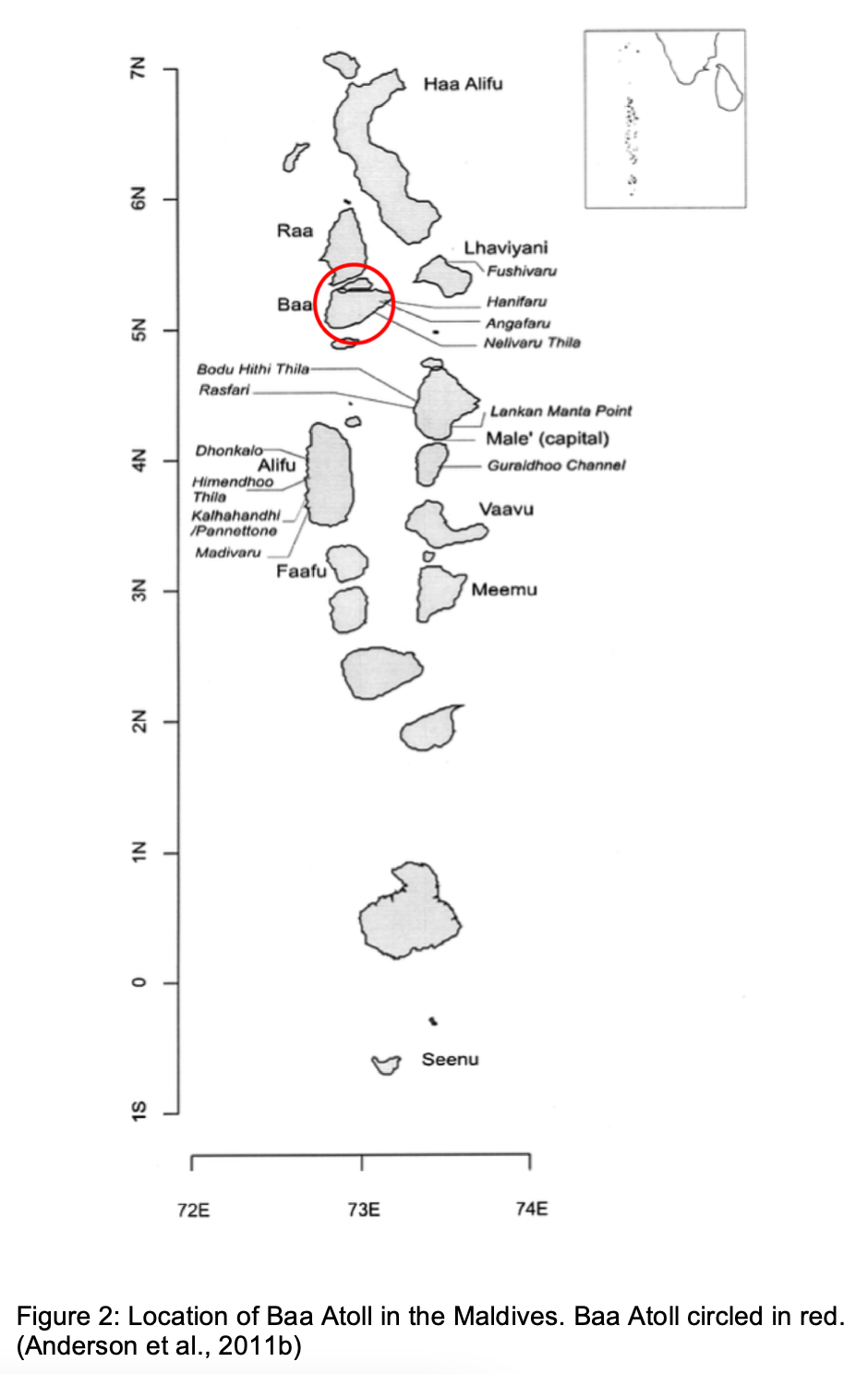

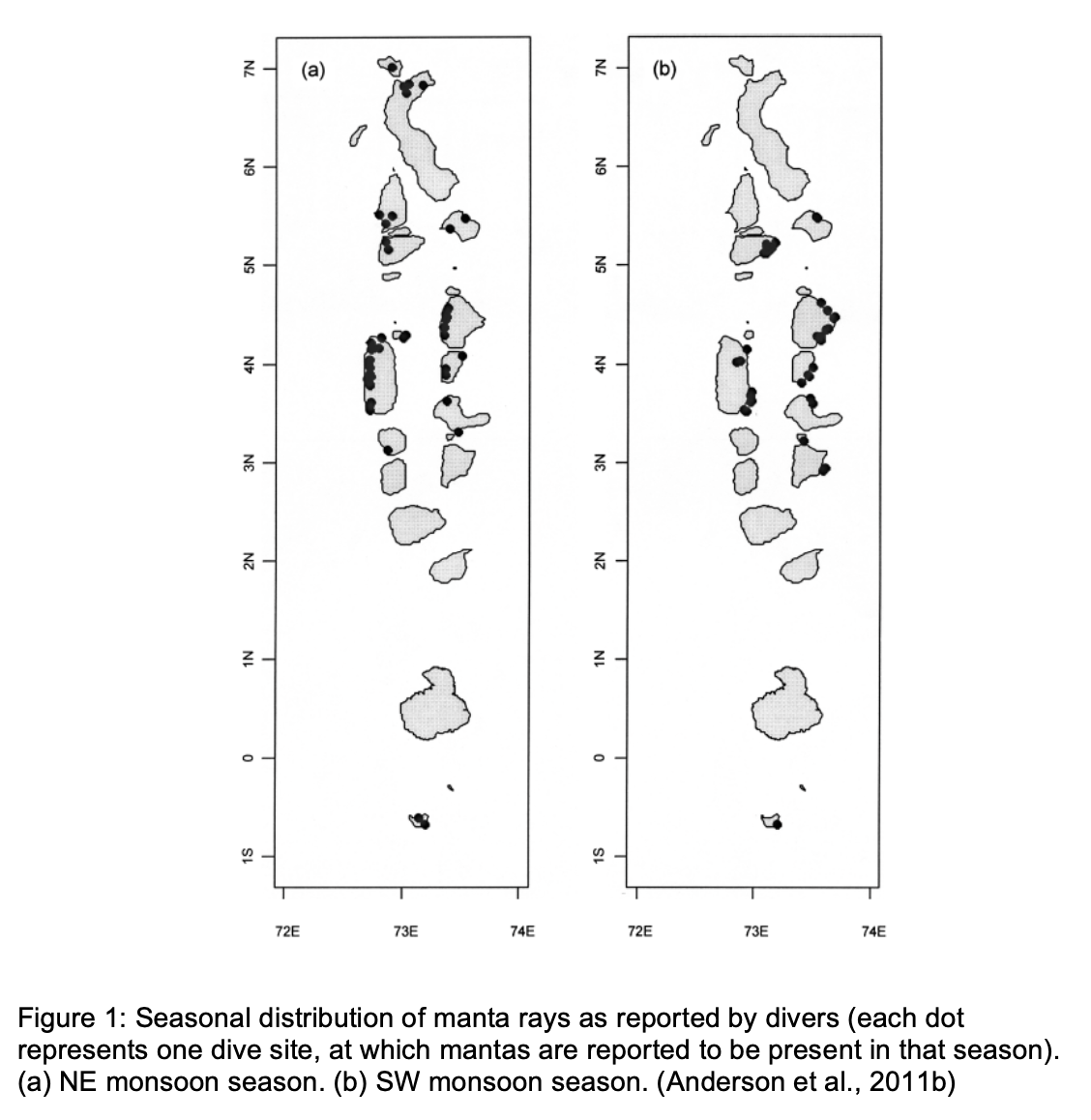

“The number of tourists travelling to the Maldives specifically to swim with charismatic marine megafauna has increased over recent years. Manta ray tourism in the Maldives is estimated to be worth US$8.1 million annually in direct revenue alone. This type of tourism clearly has significant benefits to the Maldivian economy but there is anecdotal evidence that large numbers of tourists at popular dive and snorkel sites is having a negative impact on reef manta rays’ natural behaviour.

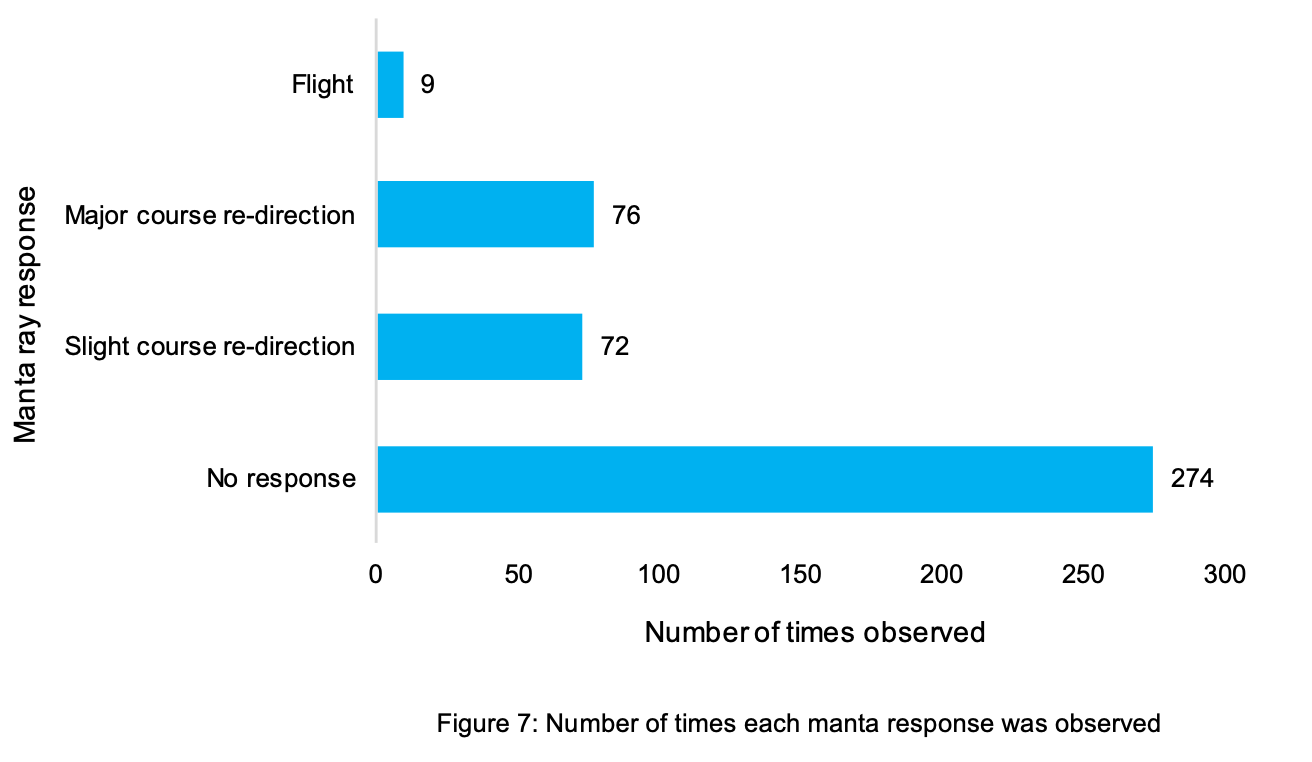

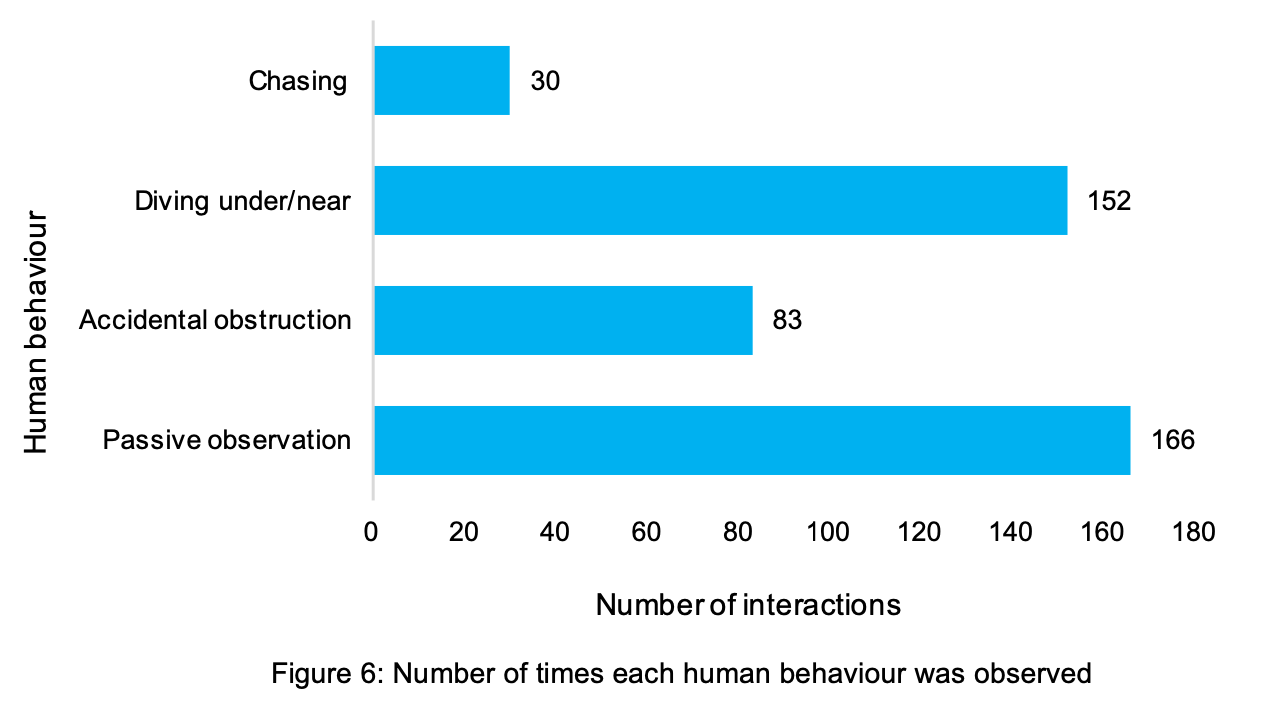

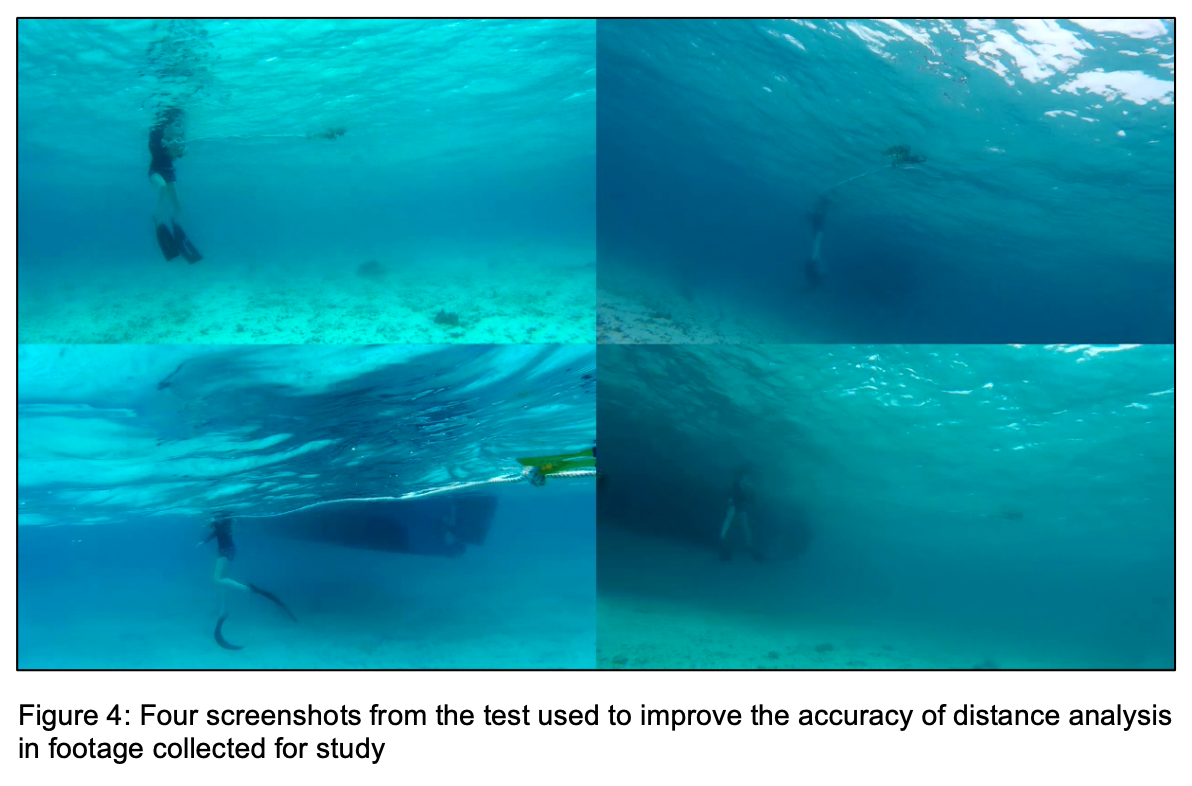

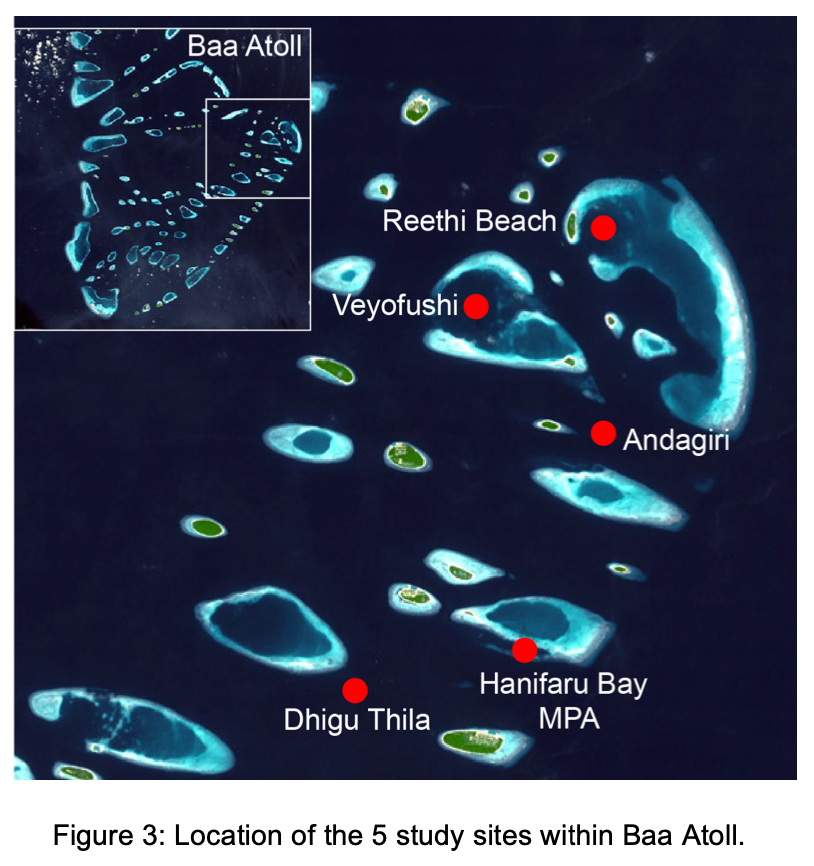

This study investigated human and manta ray tourism interactions by collecting video footage (n = 431) over a two-month period in Baa Atoll, Maldives at five feeding aggregation sites, to identify and quantify how human in-water snorkelling conduct affected the manta rays’ feeding behaviour.

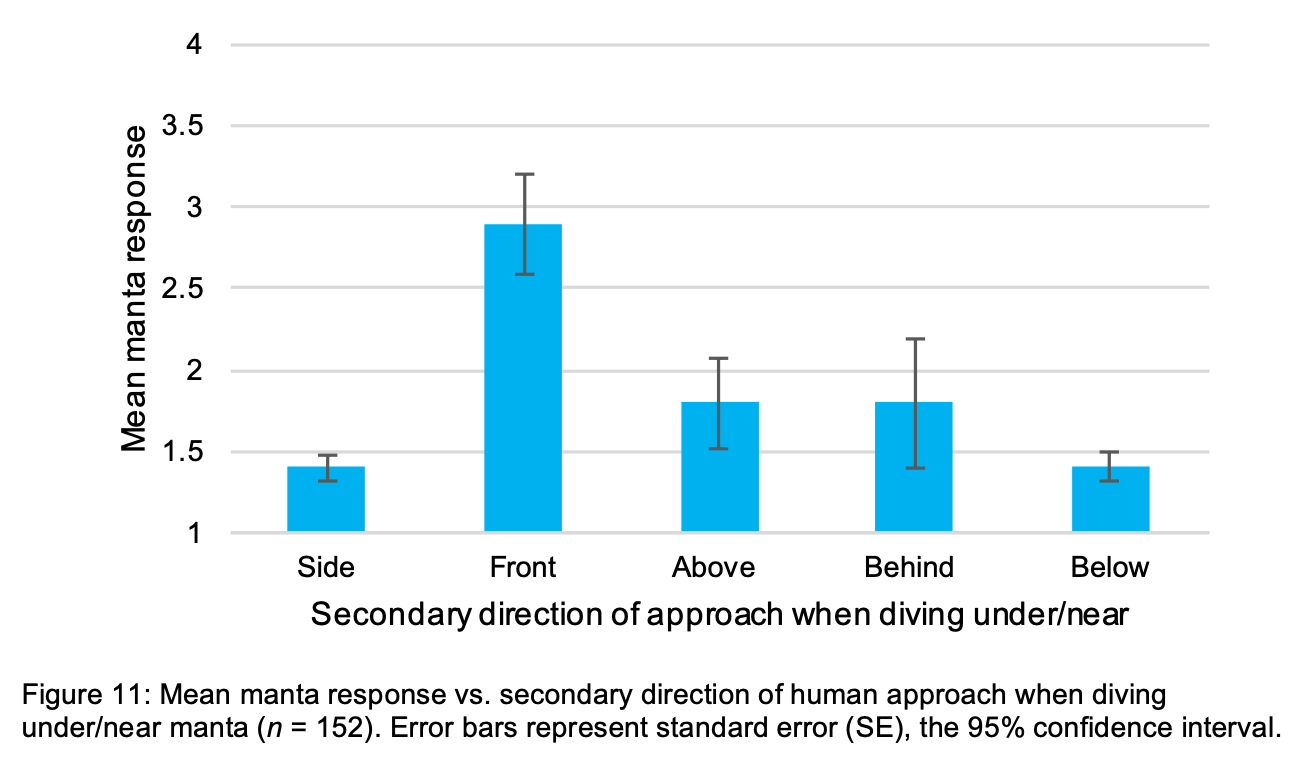

Passively observing the manta significantly decreased the likelihood of causing a strong reaction from the manta. Accidentally obstructing the path of the manta significantly increased the likelihood of the manta displaying avoidance behaviour as did approaching the manta from the front. Tourists positioned between 0 and 3 m of the manta significantly increased the probability of avoidance behaviour from the manta. Diving under/near mantas from the front strongly increased the probability of avoidance behaviour from the manta. Mantas recorded at sites where juveniles are regularly observed also reacted more strongly to human behaviour.These findings reveal key recommendations: (1) tourists should observe mantas passively, (2) a minimum of 3 m distance should be maintained between human and manta, (3) approach from the side of the focal manta ray, (4) inexperienced snorkelers should not dive underneath or near manta rays, (5) tourists should not dive in front of mantas, (6) at sites where juveniles are regularly sighted, be more cautious when approaching manta rays. All results and recommendations support the Manta Trust Code of Conduct for Tourism Interactions.”

Author Affiliations

University of York

The Manta Trust