Novel applications of animal-borne Crittercams reveal thermocline feeding in two species of manta ray

December 2019

Joshua D. Stewart, Taylor T. R. Smith, Greg Marshall, Kyler Abernathy, Iliana A. Fonseca-Ponce, Niv Froman & Guy M. W. Stevens

Keywords: Mobula birostris • Mobula alfredi • Mexico • Maldives • Mobulid • Feeding Ecology

Summary: Oceanographic fronts and pycnoclines are important for predator and filter feeder foraging. Manta rays depend on mesopelagic and non-surface zooplankton prey. Researchers used animal-borne video cameras to observe manta ray feeding behaviour at depth. Feeding occurred near the thermocline, suggesting its importance. However, non-feeding and social behaviours also took place there. The study discusses attachment methods for the cameras and their potential applications.

Abstract

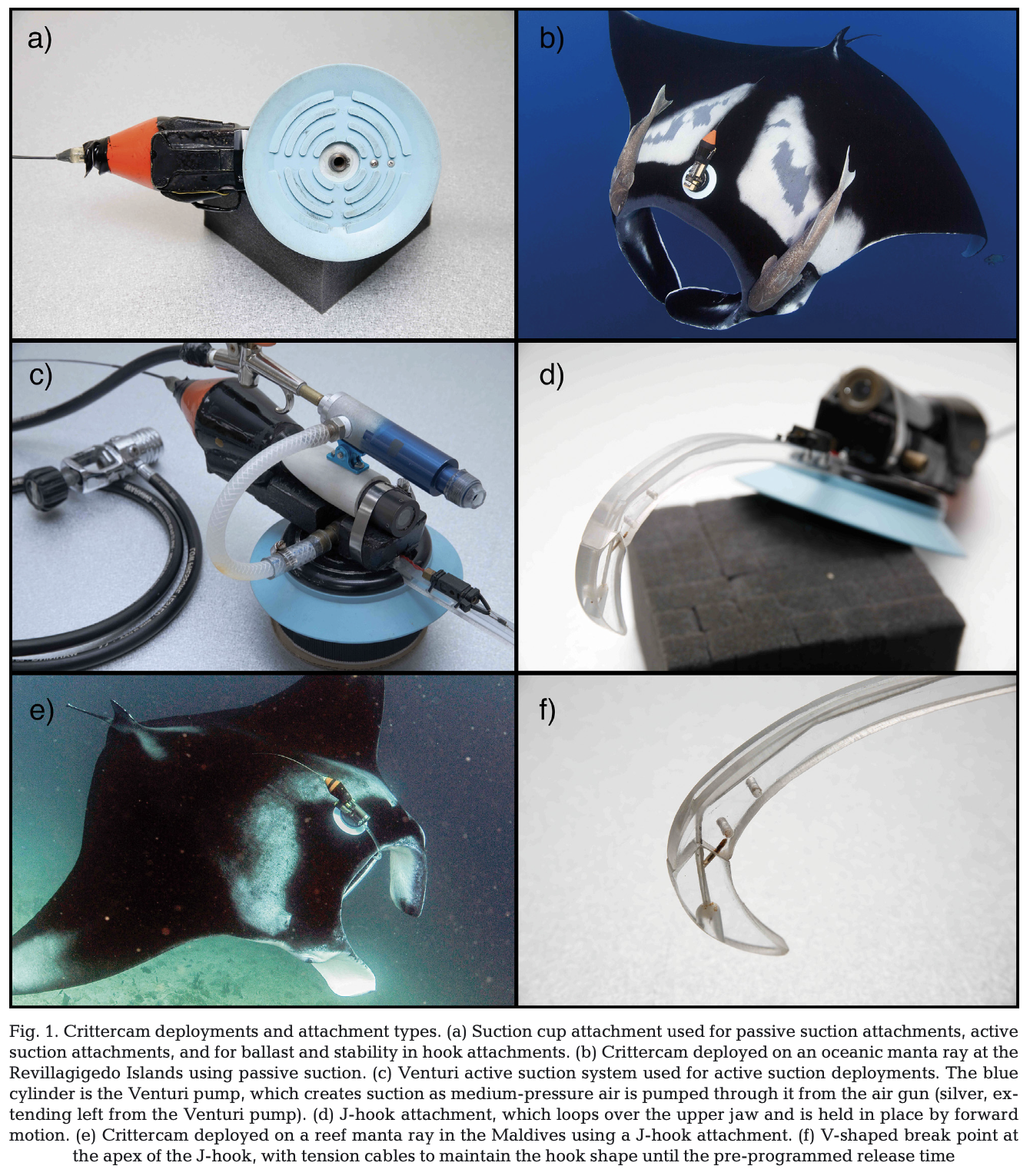

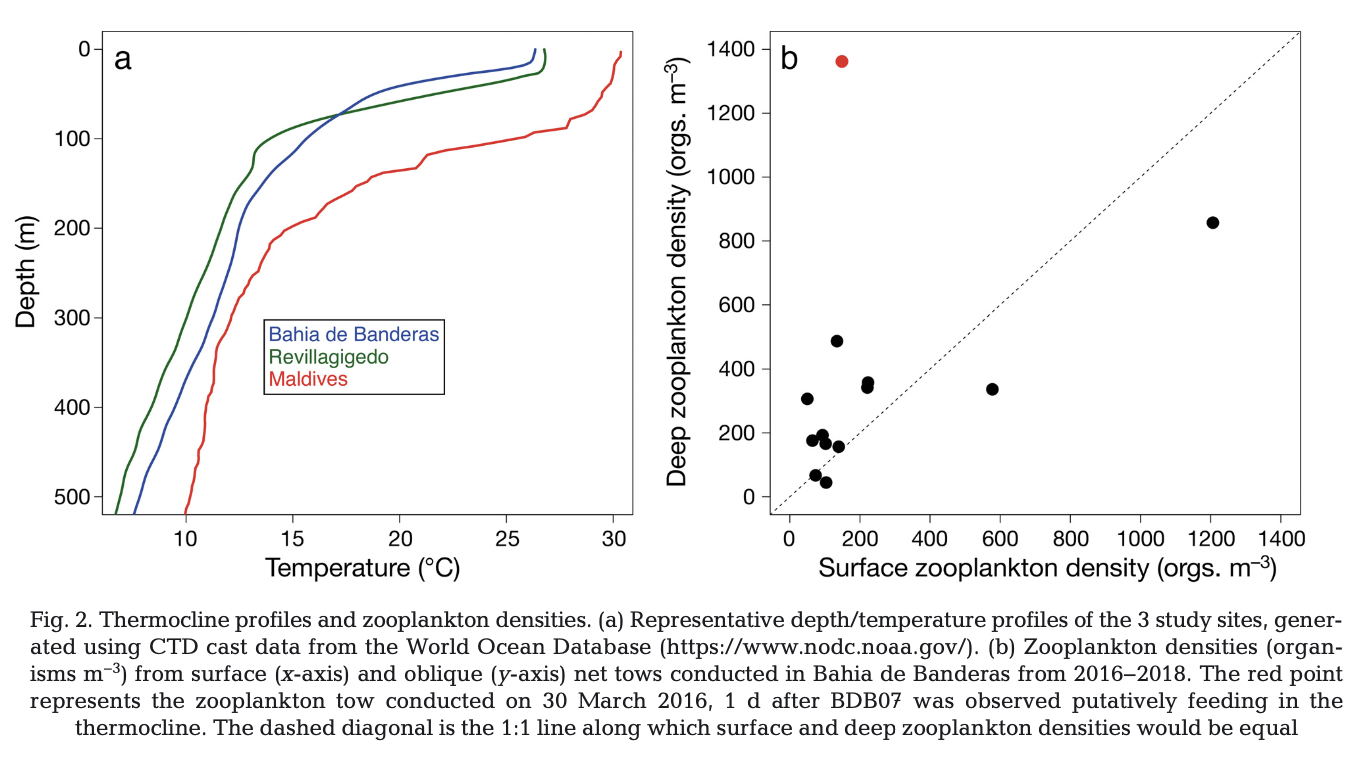

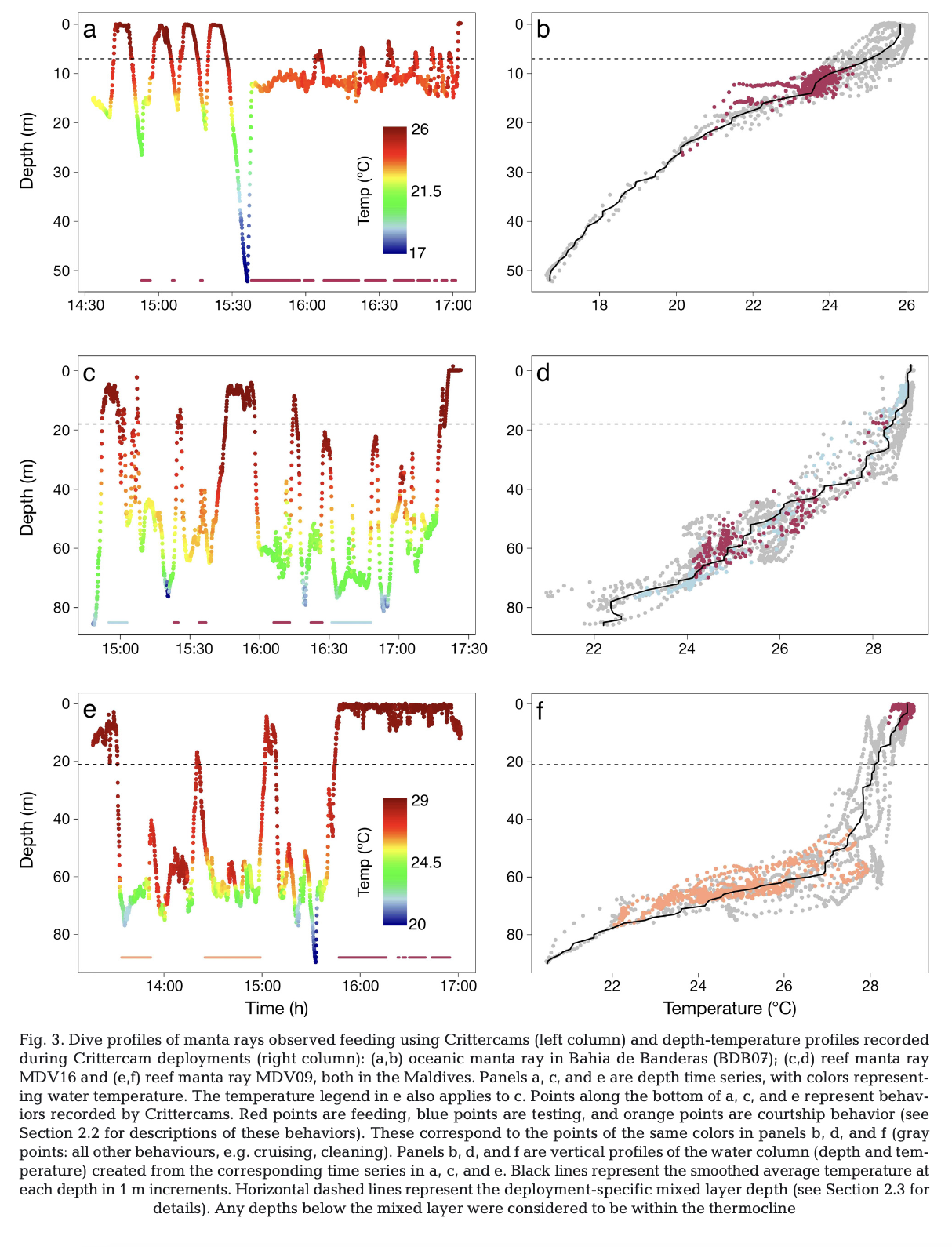

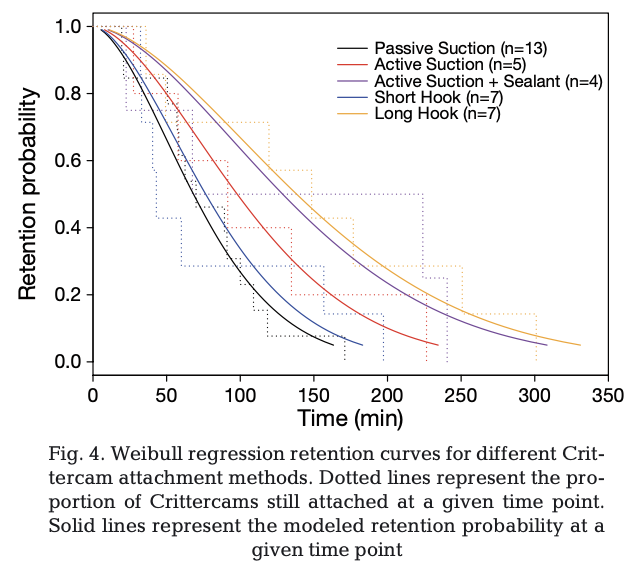

“Many marine species rely on oceanographic processes to aggregate prey sources and facilitate feeding opportunities. Numerous studies have demonstrated the importance of oceanographic fronts in the movement and foraging ecology of both predatory and filter feeding marine species. Fewer studies have investigated the importance of vertical pycnoclines (e.g. ther- moclines) as foraging queues and prey aggregators. Manta rays, large batoid filter feeders, are be- lieved to rely heavily on mesopelagic and non-surface associated zooplankton prey based on telemetry data, stomach contents, stable isotope, and fatty acid analyses. However, few direct ob- servations exist of non-surface feeding in manta rays. We developed minimally-invasive attach- ment methods for animal-borne video cameras (‘Crittercams’) on 2 species of manta ray in Mexico and the Maldives, with the objective of capturing feeding behavior at depth. We achieved reten- tion times of up to 4 h using an active suction attachment with a sealant in oceanic manta rays, and up to 5 h using a J-hook attachment on the upper jaw of reef manta rays. We observed feeding by both species on high-density zooplankton prey that was associated with the thermocline, suggest- ing that this prey aggregator may be important to the foraging ecology of both species. However, we also captured a variety of social and non-feeding behaviors that occurred within the thermo- cline, suggesting that telemetry-based temperature and depth data alone cannot facilitate an evaluation of the relative importance of thermocline-associated feeding. We analyzed the impact of different attachment methods on camera retention time, and discuss other relevant applications of these minimally-invasive attachment methods.”

Author Affiliations

Scripps Institution of Oceanography

The Manta Trust

Department of Biological Sciences, California State University

National Geographic Remote Imaging Program

Marshall Innovation LLC

National Geographic Exploration Technology Lab

Instituto Tecnologico de Bahia de Banderas

Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas (CICIMAR-IPN)

Proyecto Manta Pacific Mexico

Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge

Funded by

National Geographic Waitt Grant

Save Our Seas Foundation

Four Seasons Resorts Maldives